Transhumanism : a possible future ?

Transhumanism Is Inevitable

"Transhumanism is becoming more respectable, and transhumanism, with a small t, is rapidly emerging through conventional mainstream avenues," Eve Herold reports in her astute new book, Beyond Human. While big-T Transhumanism is the activist movement that advocates the use of technology to expand human capacities, small-t transhumanism is the belief or theory that the human race will evolve beyond its current physical and mental limitations, especially by means of deliberate technological interventions. As the director of public policy research and education at the Genetics Policy Institute, Herold knows these scientific, medical, and bioethical territories well.

Movements attract countermovements, and Herold covers the opponents of transhuman transformation too. These bioconservatives range from moralizing neocons to egalitarian liberals who fear the new technologies somehow threaten human dignity and human equality. "I began this book committed to exploring all the arguments, both for and against human enhancement," she writes. "In the process I have found time and again that the bioconservative arguments are less than persuasive." (Herold cites some of my own critiques of bioconservatism in her book.)

Herold opens with a tale of Victor Saurez, a man living a couple of centuries from now who at age 250 looks and feels like a 30-year-old. Back in dark ages of the 21st century, Victor was ideologically set against any newfangled technologies that would artificially extend his life. But after experiencing early onset heart failure, he agreed have a permanent artificial heart implanted because he wanted to know his grandchildren. Next, in order not to be a burden to his daughter, he decided to have vision chips installed in his eyes to correct blindness from macular degeneration. Eventually he agreed to smart guided nanoparticle treatments that reversed the aging process by correcting the relentlessly accumulating DNA errors that cause most physical and mental deterioration.

BeyoundHumanCoverStMartinsPress

St. Martin's Press

Science fiction? For now. "Those of us living today stand a good chance of someday being the beneficiaries of such advances," Herold argues

Consider artificial hearts. In 2012 Stacie Sumandig, a 40-year-old mother of four, was told that she would be dead within days due to heart failure caused by a viral infection. Since no donor heart was available, so she opted to have the Syncardia Total Artificial Heart (TAH) installed instead. The TAH completely replaces the natural heart and is powered by batteries carried in backpack. It enabled Sumandig to live, work, and take care of her kids for 196 days before a donor heart became available. As of this month, 1,625 TAHs have been implanted; one person lived with one for 4 years before receiving a donor heart. In 2015, an ongoing clinical trial began in which 19 patients received permanent TAHs.

Herold goes on to describe pioneering research on artificial kidneys, livers, lungs, and pancreases. "Artificial organs will soon be designed that are more durable and perhaps more powerful than natural ones, leading them to become not only curative but enhancing," she argues. In the future, people will be loaded up with technologies working to keep them healthy and alive. (One troubling issue this raises: What do we do when someone using such biomedical technologies chooses to die? Who would be actually be in charge of deactivating those technologies? Would the law treat deactivation by a third party as tantamount to murder? In such cases, something akin to today's legalized physician-assisted dying may have to be sanctioned.)

Artificial organs have considerable competition too. Herold, unfortunately, does not report on the remarkable prospects for growing transplantable human organs inside pigs and sheep. Nor does she focus much attention on therapies using stem cells that could replace and repair damaged tissues and organs. But such research supports her view that biotechnologies, information technologies, and nanotechnologies are converging to yield a plethora of curative and enhancing treatments.

The killer app of human enhancement is agelessness—halting and reversing the physical and mental debilities that befall us as we grow old. Herold focuses a great deal of attention on the development of nanobots that would patrol the body to repair and remove the damage caused as cellular machinery malfunctions over time. She believes that nanomedicine will first achieve success in the treatment of cancers and then move on to curing other diseases. "Then, if all goes well, we will enter the paradigm of maintaining health and youth for a very long time, possibly hundreds of years," she claims. Perhaps because research is moving so fast, Herold does not discuss how CRISPR genome-editing will enable future gerontologists to reprogram old cells into youthful ones.

Herold thinks these technological revolutions will be a good thing, but that doesn't mean she's a Pollyanna. Throughout the book, she worries about how becoming ever more dependent on our technologies will affect us. She foresees a world populated by robots at our beck and call for nearly any task. Social robots will monitor our health, clean our houses, entertain us, and satisfy our sexual desires. Isolated users of perfectly subservient robots could, Herold cautions, "lose important social skills such as unselfishness and the respect for the rights of others." She further asks, "Will we still need each other when robots become our nannies, friends, servants, and lovers?"

There is also the question of how centralized institutions, as opposed to empowered individuals, might use the new tech. Behind a lot of the coming enhancements you'll find the U.S. military, which funds research to protect its warriors and make them more effective at fighting. As Herold reports, the Defense Advance Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is funding research on a drug that would keep people awake and alert for a week. DARPA is also behind work on brain implants designed to alter emotions. While that technology could help people struggling with psychological problems, it might also be used to eliminate fear or guilt in soldiers. Manipulating soldiers' emotions so they will more heedlessly follow orders is ethically problematic, to say the least.

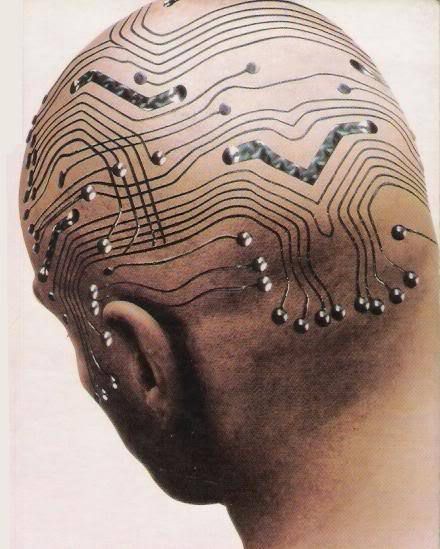

Similar issues haunt Herold's discussion of the technologies, such as neuro-enhancing drugs and implants, that may help us build better brains. Throughout history, the ultimate realm of privacy has been our unspoken thoughts. The proliferation of brain sensors and implants might open up our thoughts to inspection by our physicians, friends, and family—and also government officials and corporate marketers.

Yet Herold effectively rebuts bioconservative arguments against the pursuit and adoption of human enhancement. One oft-heard concern is that longevity research will result in a nursing-home world where people live longer but increasingly debilitated lives. That's nonsense: The point of anti-aging research is not to let people be old longer, but to let them be young longer. Another argument holds that transhuman technologies will simply let the rich get richer. Herold notes that while the rich almost always get access to new technologies first, prices then come down quickly, making them available to nearly everyone eventually. She is confident that the same dynamic will apply to these therapies.

Bioconservatives often assert that enhancement technologies must be banned because that they and theirs will experience irresistible social pressure to use them just to stay competitive. Herold tartly replies, "It's every individual's responsibility to make choices that he feels are good for him. It's not society's responsibility to limit the freedom of other people so that one can feel good about his choices." Bioconservaties, she notes, "fail to make a case for why those who oppose enhancement should be able to exercise free choice while those who desire it should not."

What about concerns about authenticity and dehumanization? Here Herold quotes me: "Nothing could be natural to human beings than striving to liberate ourselves from our biological constraints." Herold observes that no one has ever really come up with a good definition of human nature. As we embark on the inevitable transhumanist journey, she correctly concludes that "we may only ever see who we are today in the rearview mirror, from a state far more advanced than where we find ourselves now." Let's go find out who we really are.

Les humains, ces «transhumains»? Le débat interdit

Depuis quelques mois, l'évolution du traitement du transhumanisme dans les médias est assez édifiante. Après une réaction inquiète ou méprisante pour cette idéologie futuriste -qui entend favoriser l'avènement d'une humanité nouvelle par la modification technologique accélérée de son corps et de son esprit-, les principales thèses du transhumanisme sont peu à peu considérées comme devant être discutées. Cette évolution est positive car il faut, en effet, débattre du et avec le transhumanisme! Ne pas laisser cette idéologie seule dessiner notre avenir, comme cela semble être le cas pour des acteurs de la nouvelle économie aux confins du numérique et du biologique qui, de la Californie aux rives de l'Asie, rêvent de faire de l'homme un être immortel ou à tout le moins de «tuer la mort».

Mais ce débat doit se tenir dans le cadre des règles de pensée communes, et non dans le cadre des règles de pensée du transhumanisme. Or, certaines thèses du transhumanisme s'installent peu à peu dans le langage commun par la mise en place d'un forçage des mots qui génère un forçage du raisonnement. Je voudrais prendre deux exemples.

«L'homme déjà transhumain»

De plus en plus, circule l'idée que nous sommes déjà des transhumains car, en portant des lunettes, des pacemakers, en prenant des médicaments pour réguler notre humeur, etc, nous utilisons des technologies qui transforment nos corps. Il n'y aurait pas lieu de craindre le transhumanisme car au fond, depuis l'invention des premiers outils, l'homme aurait toujours été transhumain. Les anthropologues nous montrent bien les métamorphoses du corps humain depuis son redressement vertical, la libération du pouce, l'évolution de la forme de son crâne, etc. Si telle est l'idée, pourquoi inventer un nouveau terme? Pourquoi qualifier de «transhumain» ce qui est si «humain»?

Une première hypothèse est que cela permet de proposer un récit qui donne sens aux considérables investissements financiers dans certains secteurs du développement technologique. Le transhumanisme joue le rôle de storytelling pour offrir à des entreprises un discours qui donne sens à leur travail, pour mobiliser les crédits publics, peut-être pour séduire des consommateurs en leur proposant un avenir radieux et, sans doute, guérir le vague-à-l'âme d'entrepreneurs devenus milliardaires et qui se demandent «pour quoi faire?»…

Il est une autre hypothèse, bien plus inquiétante: en procédant ainsi, les transhumanistes utilisent une stratégie linguistique maintes fois éprouvée, celle de renommer l'ancien pour mieux faire accepter l'inédit. Poser le débat dans ces termes signifie que la transgression du transhumanisme n'en est pas une. Cette stratégie rejoint d'ailleurs celle qui, dans leurs argumentaires, leur fait se trouver dans le passé des prédécesseurs, comme Pic de la Mirandole ou Francis Bacon, non sans déformer leur pensée par ailleurs. Qu'il soit rhétorique ou linguistique, il s'agit d'un forçage des termes qui fausse le débat. Comment discuter de la transgression transhumaniste si elle avance masquée? En effet, si on définit comme étant «transhumain» tout usage de la technologie, alors la moindre critique du transhumanisme devient une critique de la technologie et, partant, de l'humain.

«L'augmentation de l'humain»

Ce forçage en rejoint un autre, de plus en plus fréquent, avec la formule «augmentation de l'humain» -en anglais «human enhancement». Cette formulation est de plus en plus reprise, sans en mesurer le raccourci implicite qui engage celui qui parle: car il s'agit d'augmenter «les capacités» de l'humain, et non d'augmenter l'humain lui-même. Cela va sans dire, me répondrez-vous. Seulement, je ne crois pas que cela aille sans le dire car, de le dire ou non, cela n'a pas le même sens. «Augmenter l'humain» implique une certaine conception de l'humain, réduit à l'addition de ses capacités et de ses compétences. «Augmenter l'humain» véhicule une vision quantitative de l'humain qu'il serait possible d'évaluer, de mesurer, de bigdatater… Certes, le transhumanisme ne fait que caricaturer ce que nos systèmes politique, économique et scolaire font de plus en plus en passant leur temps à évaluer les compétences et à oublier la personne qui leur donne sens. Non, l'humain ne peut pas être «augmenté». Seules ses capacités peuvent l'être. Le transhumanisme n'entend pas seulement soutenir l'usage de la technologie par l'homme, il entend remplacer la vie humaine par la croissance technologique, en laissant croire qu'avoir ou pouvoir plus permettra d'être plus.

Cette vision me semble contaminer d'autres usages linguistiques, au-delà du transhumanisme comme la distinction entre l'«augmentation» et la «réparation» de l'humain. Poser ainsi le débat réduit la pensée à une alternative qui n'est pas si large qu'il pourrait sembler. Peut-on passer sans perte du soin à la réparation de l'humain? Réparer ou soigner, est-ce la même chose? Tenir tout acte médical pour une réparation est un glissement vers une conception de l'homme comme agrégat, somme, quantité, et non comme qualité d'être.

Ces forçages font de l'identification de l'humain au «transhumain» un a priori de toute discussion sur le transhumanisme. Entrer dans ce jeu fait de quiconque avancerait des arguments contraires au transhumanisme un technophobe et un anti-humain. Déjà, Humanity +, la fédération transhumaniste mondiale, défend l'idée que la «liberté morphologique» de chacun -entendez le droit de chacun d'utiliser, sans aucune restriction, les technologies pour transformer son corps- devienne un droit fondamental. Et que toute discussion de ce «droit» soit une attitude «technophobe» et donc discriminatoire. On mesure aisément comment ce type d'argument peut être utilisé par des industriels et des scientifiques soucieux de s'émanciper des lois de bioéthique et de tout contrôle par la loi ou l'État de leur action.

Alors, débattons du et avec le transhumanisme, mais débattons en pensant aux mots utilisés. Le transhumanisme, comme toute idéologie, entend transformer notre vision du monde et de nous-même pour nous faire accepter son projet social et politique. Et changer le sens des mots est la première chose que fait une idéologie pour changer une vision du monde... Peut-être sommes-nous appelés à devenir transhumain, peut-être devons-nous choisir de le devenir, mais dire que nous sommes déjà transhumains fausse le débat et empêche de choisir. Par contre, nous serons à coup sûr transhumanistes si nous disons le monde avec les mots de l'idéologie transhumaniste. Il faut en prendre conscience pour débattre - en toute liberté de raison - de notre avenir.

Hi everyone,

Today on InnovaTech Review, I will comment two articles on transhumanism. If you never heard about it, it is the enhancement of Human’s capacities with technology. This might seem quite unrealistic but it is becoming a reality: a lot of big companies and governments have already started researches about how they could make our brains faster, our muscles stronger, etc ...

The first article from the American magazine Reason is a commentary about Eve Herold's book " Beyond Human: How Cutting-Edge Science Is Extending Our Lives ".

The second one comes from the French newspaper Le Figaro, and wants to establish a debate between the conservative vision and the Transhumanists.

Both of these articles agree on the fact that technology cured a lot of people and is really useful in the medicine field. But transhumanism raise an ethical question: should we interfere with our nature, and become what Science-fiction called Cyborgs ? There is also a problem of equity, technologies like this are really expensive and will be most likely to enlarge the gap between the poor "simple" human and the rich "enhanced" human.

Like I said, this will become a reality in a closer future than you think, nano-techs for instance are a big hope in many fields of researches and could be used in order to make us live longer by repairing tissues or immunize us against most of the diseases. The case of the artificial heart which has proven that it worked is an important step on the road to transhumanism because if we can replace an organ, why not replace it with better capacities ?

Of course, we still have time before these technologies become available for the public, like the brain connected to the internet, and governments shouldn't wait to elaborate laws and rules to supervise this. With a lot of good aspects, transhumanism has on the other hand many gray areas, the possibility for governments to collect datas directly from our brains, the elimination of feelings for soldiers, ... a lot of things that could lead to dehumanization of our society.

For now, these are only hypothesis but "Those of us living today stand a good chance of someday being the beneficiaries of such advances"

/image%2F2152240%2F20160923%2Fob_e1c8a2_3-white-logo-on-color1-117x75.png)

/image%2F2152240%2F20170326%2Fob_0edfad_636260753956243084-uber-accident.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fi.ytimg.com%2Fvi%2F7A7GsAPR3J0%2Fhqdefault.jpg)

/image%2F2152240%2F20170228%2Fob_d88d6c_deep-brain-56a6f5de3df78cf772911f1f.jpg)

/image%2F2152240%2F20170130%2Fob_ef0c01_donald-trump-elections-2016-624x351.png)